AS A 16 YEAR OLD STUMBLING through a critical moment of teenage evolution, to say that Fugazi was my “favorite” band would be a reasonable admission; though, it would also be a bit of an overstatement. In my mind, they were immeasurably above the bar in terms of what I thought a band could be; how a band could sound, and what they could—and, did—stand for. It was almost as if they weren’t a band at all, but rather, an ideology; one that could be decoded if the listener paid close attention.

When word spread that they had confirmed a show in my hometown, it was not only unexpected, but completely unbelievable. I was well aware that the quartet were serious about their craft, and while traveling the corners of the earth in order to spread the message of their music was a necessary to-do, to make a stop in my un-patterned city sparked a confused bewilderment.

When the day of the show finally arrived, me and a small group of friends eagerly made our way to Bakersfield’s historic Tejon Theatre. A quiet surge of electricity permeated the car, and I could feel the excitement as it grew within me. My stomach was a hive of activity with one central objective: to reposition my guts to a state of inversion. November 7th, 1995 was primed to be a momentous evening; and, it most certainly was—for reasons I never could have predicted.

THROUGHOUT THE COURSE OF 1995, Fugazi toured relentlessly in support of their fourth studio album ‘Red Medicine,’ which was released in June of the same year. In the months since I sat in front of my friend’s house and listened to the album for the first time, I’d come to believe that the elevated status I’d awarded the group had effectively—albeit, inadvertently—branded them with a massive Target, and my outspoken contempt for the album was a strike between the eyes of a colossal titan.

I managed to walk into the show excited, though I wasn’t necessarily convinced that a performance laced with songs I didn’t want to hear would help the band and I reconcile our differences. 30 years of introspection would suggest that the general excitement that surrounded this show was mildly overshadowed by angsty, teenage apathy—and, I do find this reflection to be accurate. I wanted to participate in the pageantry of the evening, and enjoy myself with friends, but I lacked the necessary bandwidth to truly care about much else. That it was a Fugazi show made little difference, and the significance of the moment was a moot point.

I’d drawn this band well outside the lines of music, and—to some extent—I’d redefined them as dispatch riders, amenable to me for a steady diet of information, punk rock ethos, and general morality. Still hot under the collar about ‘Red Medicine,’ my obstinate criticism regarding their latest broadcast had induced an unfamiliar static in the line, and—at the time of this particular show—I was no longer interested in listening.

In addition to the weight of internal burden, there were two externalities that awaited my attendance, and both were largely unavoidable:

1. Sound quality. I’d been to three shows at The Tejon, and each one sounded like absolute garbage.1 Frequencies on the higher end of the spectrum pierced through earplugs like lightening strikes, while a low-end swamp rumbled through the space like a torrential mudslide. Kick drum blasts bounced around the room like a rack of basketballs falling through an ill-synced delay unit, and the vocals might have well been sung from the inside of an aluminum trashcan. It was an atrocious venue for live music, and I wasn’t looking forward to the aural abuse.

2. Skinheads. While a majority of the Bakersfield skinhead community were SHARP2 skins, their inclination toward general troublemaking and Neanderthalic violence was annoying, disruptive, and triggered by big ticket shows which summoned an excess of kids to pounce upon under the guise of “fun.” Fugazi’s outspoken rejection of testosterone driven machismo, and their refusal to provide a soundtrack for those who sought to destroy everyone’s good time with aggressive circular dancing—and, other overt displays of masculinity—provided a beacon on this occasion. Confrontation was imminent, and the dregs slithered out of the woodwork and descended on The Tejon like a plague. At least a half-dozen “interludes” commenced in the group’s attempt to instill some sense of order, but to no avail.3 Spit flew, middle fingers and insults were thrown, and the dreaded security barricade at the front of the stage collapsed under a mass of chaos. It was a shit-show, and from my perspective, it was a fucking embarrassment.

BEFORE THE SHOW BEGAN, I posted up behind the last row of seats at the rear of the theatre, directly next to a set of doors. I was comfortable with my position, which enabled me to chew the rag with friends as they oscillated between the show space and the theatre’s massive lobby. It was a relatively comfortable vantage point, and I remained there for the entirety of the evening; safe enough from the violent throng.

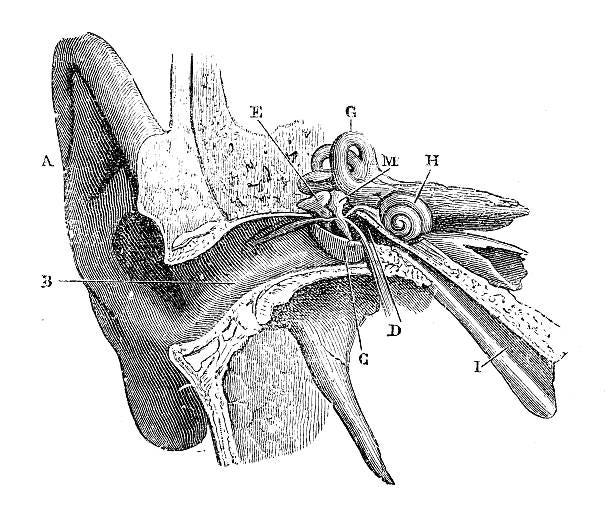

Memorative contemplation and recurrent experience allows me to profess—with a certain degree of confidence—that Fugazi played a worthwhile set, though I wouldn’t hold the statement over my head as definitive fact.4 Aside from the uncharacteristic warbly-ness of Guy’s voice,5 the overall performance of the evening occupies very little real estate in my manor of recollection. All that remains is a slow-motion dance of familiar bodies as they strut across a plank of memory, almost as if walking under water. And, this lapse has little to do with the deterioration of my entorhinal cortex; instead, it has everything to do with a band called The Warmers.

APPEARING OUT OF THIN AIR in the spring of 1994, The Warmers were completely unknown to the Bakersfield scene at the time they took the stage. The theatre was still—mostly—empty, and a calm, Provisional fête had settled upon the venue.6 As the Turnover music that coursed through the PA slowly faded to a distorted whisper, the trio approached their instruments, which were dwarfed by the massive platform. Taken aback by their slick manner of dress, I focused my attention curiously, as their overall aesthetic winked at the seductive style of another DC outfit known as The Nation of Ulysses.7

In an instant, a hopeless expectation sparked within me, and I held my breath in anxious anticipation as I awaited an echo of the frenetic energy that had defined The Sound of Young America. However, the music I was presented with—while not a strict dichotomy—was strange, unusual, and laced with contrariety. Within the first few bars of their set, a prismatic shift of perspective offered a sweet antithesis to the grinding hardcore of the day, and I stood frozen as The Warmers completely blew my mind with their unique brand of permutated avant-punk.

The group’s ability to maintain a consistent stream of dynamic interplay without leaning on the crutch of gratuitous amperage immediately captured my interest. Fits and starts of volume and rhythm tickled the senses, and the unpredictable meandering of their music demanded attention. Through a malformed adjacency to mere simplicity, their minimalist approach to post-hardcore was a beautiful rats nest of convolution, and by enticing one to take the long way home, The Warmers completely seized control of the room. Their greatest asset in this spacial commandeering was the clever use of space itself, which was played as if it were an instrument in its own right. The resultant set was a choppy exercise in sonic angularity, and after just a handful of songs, what I Wanted: More.

From the perch of my makeshift haven at the rear of the theatre, the music that emanated from the stage was like an alien transmission, and I absorbed every note like a thirsty sponge. Subtle nods to the past offered a bite-sized taster’s menu that prepared my palate for the future, and I dreaded the set’s inevitable conclusion. Throughout the course of the event, a subconscious reinvigoration of dejected spirit had taken place, which left me punch-drunk and hazy-eyed; enamored with the possibility of growth in a community that seemed somewhat paralyzed by regulation. Overcome by the unexpected ebullience, it was precisely this haziness that hindered my ability to focus as the show progressed—which effectively cloaked the headlining act we’d all stood on line to see. I wouldn’t propose that Fugazi were “blown off the stage” that evening, but while in the midst of a brown study, a little voice inside my head uttered three words: “Exuent, gentlemen! Exuent!”

A BRIEF EXAMINATION OF PERSONNEL is important to note, in spite of the potential blunder that language presents in the face of concepts such as alchemical connection—which was quite apparent in this amalgamation of souls. Atypical in a world enriched with generalization and genre-defined categorization, The Warmers carved out an off-center dwelling where their unique sound could thrive within the space they nurtured and embraced.8

Alec Mackaye • Alec has maintained his well deserved status in the DC scene, which survived alongside the immense shadow cast by his older sibling, as opposed to beneath it. Having made a name for himself at a very young age as the voice of The Untouchables, Alec went on to front The Faith in 1981, followed by Ignition in 1986—two highly influential, if not legendary DC outfits.9 Donning a guitar for the first time at the onset of The Warmers, Mackaye’s greenhorn technique encompassed a scratchy percussive style, wrought with cyclical melodic lines; an apt, minimalist counterpoint to the group’s knotty rhythmic dynamism.

Juan Luis Carrera • Aside from his previous work with singer/songwriter Lois Maffeo—and, a reputable list of engineering credits—Juan’s overall career is nebulous at best.10 However, his contribution to The Warmers was imperative to their overall sound; both vocally, and by way of his impressive, rhythmic mobility.

Amy Farina • According to a relatively uncertain—and, mildly patronizing—Trouser Press review,11 Douglas Wolk referred to Amy as “a drummer under the occasionally fortuitous impression that [she’s] John Bonham”—though, I’m somewhat convinced that Wolk made this absurd comparison while looking down his smug nose. Fellow musicians have described Amy’s drumming as “furious” and “bombastic,” and while I’m inclined to agree, to define her idiosyncratic style in such a vestigial way is a bit of an oversimplification. Her contribution to The Warmers is nothing short of otherworldly, and her singular technique deserves deeper analysis.

On the face of it, Amy’s patterns are not overly complicated, but the odd, disjointed nature of her playing imbues a peculiar momentum, which often feels like an antagonistic headbutt to conventional rhythm. Her unorthodox use of negative space is sharp-cornered and dissonant, though impassioned fluidity never suffers at the altar of sacrifice. And, whereas Bonham intentionally played behind the beat in order to create the illusion of tension—by way of studio trickery—Amy plays with the very breath of the beat itself, which is built entirely upon the space she creates for it. This unusually effective fusion of musicality and instability is utterly intoxicating, and it’s precisely what sets Amy apart from the average—if not, every—player.

As always, thanks for coming out!

If you enjoy what we’re doing and want top-notch exclusive content, there’s no time like the present to slip backstage—become a paid subscriber!

Below the footnotes, two additional videos exist for which to sink your eyes and ears into. And, to anyone and everyone equipped with a VIP access pass, we appreciate your support very much.

The first time I stepped inside The Tejon was for a midnight screening of ‘The Rocky Horror Picture Show,’ complete with shadow cast and optional prop bag! The first band I saw there was Samiam in 1994, then the theatre temporarily closed. After the grand reopening, two massive acts were booked for the month of August, 1995: Circle Jerks, and The Ramones.

Discovered online—via Athens, GA based magazine Chunklet—nearly 15 years ago, the embedded 45-minute collage titled ‘Having Fun On Stage With Fugazi’ was created by James Burns of Seattle’s Police Teeth. With a runtime loosely modeled on the average length of a Fugazi album, ‘Having Fun…’ casts a brilliant light on the comedic stage banter of an extremely tight knit unit, which you can enjoy now, in this very footnote!

Decide for yourself: this show has been digitized, and is available for purchase/download via Dischord’s ever expanding Fugazi Live Series.

And, roughly a third of their stage time dedicated to songs taken from ‘Red Medicine.’

After a cloddishly hilarious opening set by Dub Narcotic Sound System, a small group of meatheads—that failed miserably to thwart Calvin Johnson’s pelvic-thrust-enriched performance with awkward hostility, but managed to polarize (and, terrorize) every other show-goer with blatant hostility—funneled back into the lobby, apparently unconvinced that the next act would be worth exhausting their pent-up aggressive energy.

As opposed to the commonly appropriated—counter-culturally acceptable—bedraggled look of your average punk/hardcore youth.

According to ‘The Grand Scheme For The Fate of Things Great and Small,’ we… the cherished lambs of Ulysses are to recognize the corporeal form of the prophet, and feast heartily upon the SYLLABUS ULYSSES as if a meal, and embrace the impetus for all deeds well done.

Point 2. To dress well, as clothing and fashion are the only things which we, the kids, being utterly disenfranchised, have any control over.

In short: not before, and certainly not since… has a band sounded anything quite like The Warmers.

According to The Faith’s bio via Dischord’s website: “While Minor Threat [was] often held up as the preeminent DC band of the early years, for many of the people living [t]here, it was The Faith that they felt the strongest connection to.”

Also linked on the Dischord website is this interview with Thurston Moore, which outlines his memories of The Faith.

Juan has also had a rumored stint in the band Lungfish, though the validity of this rumor has yet to be verified.

This review is an overview of the career of singer/songwriter Lois Maffeo, who Amy worked with alongside Juan, first as touring musicians, then in the studio during the recording of ‘Shy Town,’ a 5 song EP released in 1995 via K Records.