HAILED BY RON DePasquale as “one of the longest surviving emo bands,” these seven words swung through the electronic pulses that illuminate my computer screen and landed a flaccid slap directly across my forehead. Contorted due to sheer embarrassment, my face winced at this egregious attempt to categorize the music of a truly enigmatic Baltimore outfit known as Lungfish. Of course, if expressing oneself through a cone of philosophically enlightened, politically cognizant, abstract poetry is a viable display of emotional release, Ron’s lackluster Spotify bio is defensible. But, to diminish the work of Lungfish by simply referring to them as “emo” is not only uninformed, it’s an irresponsible misalignment; as Lungfish are—for lack of a better word—unclassifiable.

To my ear (and through the lens of my third-eye), the sacred geometrical Metatron cube of genre categorization positions Lungfish at the intersection of complex minimalism, and Taoist spiritualism; for when the rubber meets the road, they not only swerve around traditional convention, they defy it.

MY FULL-FLEDGED APPRECIATION for Lungfish took root during the Fall of 1997. After several years of spotty activity on my radar, my ability to ignore the persistent blips was beginning to show cracks in its foundation. In the aftermath of a rather difficult summer tour—which ended unceremoniously in a stranger’s apartment somewhere in New Jersey—I found myself settling with the dust back in my childhood home. Jobless, penniless, and band-less, I was forced to confront the possibility that the latter point of interest brought along with it a relative friendlessness as well. I was thrust into a period of deep isolation, and while solitude wasn’t a foreign concept,1 the luxury of choice felt as though it had been completely stripped away. The future was dimly lit, and the depression that surrounded this negative prognostication had become quite difficult to navigate.

I stood precariously on the precipice of a downward spiral, and I began to feel the earth shift beneath me, unaware of what the world might look like after I’d lost my footing. Despair masqueraded as indifference, and my overall behavior was reflected in its Web Of Mirrors. I sought solace in quotidian proclivities, and a few offered dull relief. But, a dense fog had rolled in and settled upon my existence like a stubborn mule, and the weight was unbearable. I had all but succumbed to this burgeoning fate when an unexpected hand appeared through the oppressive mist. Weatherworn and heavily tattooed, the cosmic body attached to the opposite end belonged to charismatic Lungfish frontman, Daniel Higgs;2 a mystical pilgrim whose mission was to guide me away from myopic darkness and toward the Infinite Daybreak of self-discovery, meaning, and truth. Armed with a sonic backdrop woven by the cyclical guitar work of Asa Osbourne, and the trance-inducing rhythmic interplay of Mitchell Feldstein and Sean Meadows,3 I could feel the storm surge as it slowly crept over my discontent. Wholly at ease with the unexpected submersion, I silently—telepathically—begged for the light to pour in.

EVERY FEW YEARS, I take a deep-dive into their vast, mercurial discography, with each album played through many times until one refuses to leave the turntable. This seemingly random display of auricular dominance, and my subsequent focus of attention remain a mystery, and the antagonizing desire to unravel the psychological ties is of little—if any—importance.

In the infinity loop of this ritual, ‘Indivisible’ sits at Point 0; a perennial favorite. Rife with muted textures and euphoric reverie, this album summoned my interest like an insatiable Siren, and quickly became the unexpected—and, rather unlikely—soundtrack to my life.4 Paired with ‘Artificial Horizon’ and ‘The Unanimous Hour,’ these heavily rotated discs make up the trilateral jewel in the Lungfish discographical crown, at what I’ve concluded is the height of their experimental, genre-bending power.

By Fall of 1998, I’d moved backward in time with ’Talking Songs For Walking,’ which I scooped up at a discounted price from a couple of friends that were in the process of dismantling their DIY record distro.5 It was here that the contradiction surrounding the longwinded joke that the band only had one song took root, as there was clearly a line of progression between ‘Talking Songs…’ and ‘Indivisible,’ which were five years, and five albums apart. Leaning more toward the progressive end of this spectrum, I tilted my ear back to the point of departure with 1996’s ‘Sound In Time;’ a purchase that was serendipitous, as the album was a bit of a sleeper in the band’s catalog. For an album that fell—mostly—flat amongst fans upon its release, the online music magazine Pitchfork awarded it an astonishing 7.4 rating in a review of the album’s reissue in 2016.6 In the same review, Jason Heller refers to the release as, “Neither the greatest nor the most momentous Lungfish album, ‘Sound in Time’ remains an intriguing, mystifying stage of the group’s evolution toward Higgs’ ‘zero hour’—a mythic space where rest and restlessness coexist without paradox.”

THE SPACE BETWEEN 1999 and 2003 was a whirlwind of personal activity, and by this point, Lungfish were ostensibly—if not entirely—defunct. No longer on the heels of the band’s trajectory, their continued forward motion somewhat eluded me. As a result of my lapsed attentiveness, two albums slipped through the cracks of this timeframe:

1. ‘Necrophones,’ which was immediately rejected upon discovery, on the aesthetic basis of inadequate cover art.7

2. A chance encounter with my roommate’s idle copy of ‘Love Is Love’ reluctantly piqued my interest as it surveyed my presence for several days, taunting me from beneath the tinted dust cover of our living room turntable.

Brought into the home just a few days after its release, I began to play an odd game, taking mental note of the central hub in various positions as I traversed the house. In addition to observing the label’s ghostly whirl around its annular venue, I also catalogued the number of disc-flippages the album underwent, as well as how often the liner notes slipped in and out of the beautifully decorated—albeit, minimalist—record sleeve.

Initially scoffed at due to the album’s title, one afternoon as I sat on the couch, I asked myself, “Why haven’t you actually participated in the contribution of this album’s rotational milage? Have you become so calloused and cynical that you’ve purposely avoided listening to this record due to its schematic title? Are you that afraid of love?” As the questions piled up, I stood and walked over to the stereo system, flipped the record to side A, and placed the needle on the edge of the plaque. And, just like that… ‘Love Is Love’ wrapped itself around me like a warm, winter blanket.

Midway through the opening/title track, a faint tingling sensation overcame my jaw, which slowly crept upward toward my ears. As the temperature increased, my face became flush with excitement, and the subtle readjustment to my antipathetic Slip Of Existence brought tears to my eyes. As the heat radiated from my being and filled the space, I watched as the room began to vibrate; an interpretive dance number in imperfect unison with the music. Through the enzyme enriched saliva oozing from my lacrimal ducts, the thermoplastic resin appeared to liquify and mutate into a portal as the record spun around the platter. Eagerly—and, willingly—I dove headfirst into the strange abyss, undeterred by the uncertainty that awaited me on the other side. Met with stripped down instrumentation, Higgs’ abstruse meanderings roamed aimless and free in an endless pasture of his own creation; and, in a magnificent display of unbridled joy, I listened as his circuitous message stretched its legs.

It’s been twenty-one years since I sat on that couch, and ‘Love Is Love’ has—arguably—become the album I’d favor most in a discourse on superlatives. And, for the uninitiated, it is certainly the album I’d recommend if you’re interested in exploring your own Lungfishian journey—just as the end becomes the beginning.

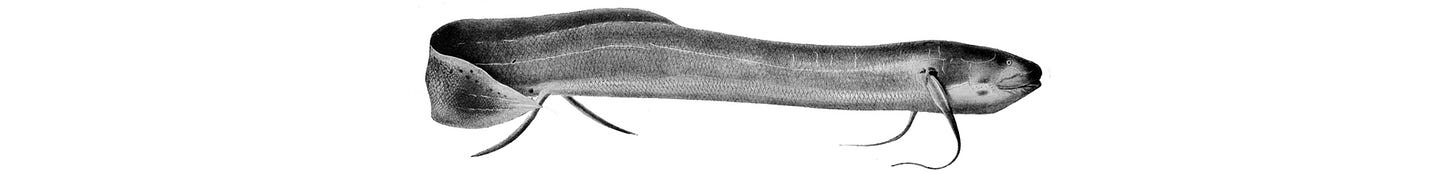

DEEP KNOWLEDGE OF THE MYTHOLOGICAL symbolism that surrounds the freshwater vertebrate is relatively unknown to me. Often linked to themes of rebirth and continuity, as a totem animal, Lungfish encourage adaptability, resilience, and transformation.8 In African art, Lungfish symbolize the cyclical nature of life, due to its ability to aestivate—or, enter a state of suspended animation—during prolonged periods of drought, reviving itself once water returns.

It’s fitting that a band bearing the name of such an evolutionary marvel would find it’s way into my life at the precise moment that it did, as both of the aforementioned historical bullet points were periods of substantial transformation and—in essence—rebirth.9

With so many great albums on tap, track selection was an exercise in manipulating the paradox of choice; especially since the band only has “one song.”

‘This World’ was taken from the album ‘Love Is Love,’ and its nebulous tone feels appropriate as we navigate the complexities of this world.

Taken from ‘The Unanimous Hour,’ the second track is meant to shine a light on the dynamic importance of the Lungfish instrumental. For a group with such a wild-eyed, charismatic frontman, the persistent inclusion of instrumental tracks—more often than not, several per album—may seem like a bootless maneuver; however, the band and its impact are no less whole as a result.

As always, thanks for coming out.

From a very early age, I was prone to increased periods of solitude, and generally preferred to spend the majority of my time alone.

AKA Daniel Arcus Incus Ululat Higgs AKA Daniel A.I.U. Higgs: Inter-Dimensional Song-Seamstress AKA DA IU HI.

As the sole transient member of Lungfish, Sean Meadows (bass) made his debut on ‘Sound In Time’ in 1996. Preceded by John Chriest, Sean was replaced by Nathan Bell for three albums between the years of 1998 and 2000. He returned in 2003 for ‘Love Is Love,’ and recorded ‘Feral Hymns’ in 2005, before the band’s eventual demise.

‘Indivisible’ was the first Lungfish album that I owned, and its status maintains a certain nostalgic bias, though not one that I’ve found to be completely unwarranted.

In the early/mid 90’s, it was quite common—and, fairly simple—for kids of any age to start a punk rock record distribution. Many of the larger punk/hardcore record labels offered wholesale prices for bulk orders, and the only prerequisite for participation was whether or not the industrious party was capable of monetary exchange. It was a beautiful grassroots operation that moved records around the country that might otherwise be disregarded by the establishment; though in truth, the establishment had been mostly rejected by the bands and labels themselves, either as a result of inexorable punk rock ethos, or lack of commercial viability.

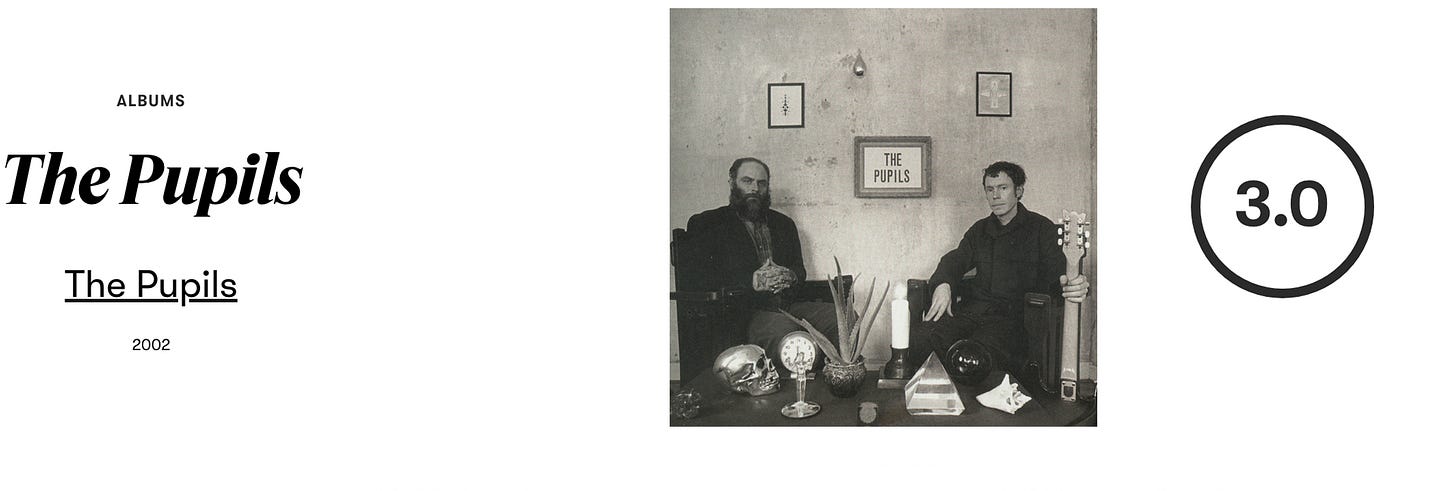

Over the years, Pitchfork has been duly criticized for serving iniquitous reviews, many of which contained a litany of factual errors, while the music itself was rarely discussed in a meaningful way. Music journalist Robert Christgau commented on Pitchfork’s overarching elitism in 2018, describing it as a “snotty boys’ club, open to many ‘critics…’ too many amateur wise-asses and self-appointed aesthetes throwing their weight around.”

Take this review of The Pupils s/t album from 2002, for example; harsh words for a fantastic album, created by 2/4 of the band they so generously praised a decade and a half later.

With several years betwixt the time of this writing and the aforementioned rejection of ‘Necrophones', the music contained on the album has certainly gained my respect and attention. The artwork… jury’s still out.

According to the website Animal Omens.

In 1997, I began to plan an exit strategy from the shackles of my hometown, which unexpectedly led me to the wonderful city of Little Rock in July of 1998.

By 2003, I had been living in Austin for three years, and in spite of the overwhelming productivity during my 37-months as a Texas resident, there was a pervasive stagnation apparent, and I was beginning to feel the pull of its current. Within two weeks of the ‘Love Is Love’ listening party on my roommate’s couch, I’d crammed everything I owned into a U-Haul trailer and hitched it—precariously—to the bumper of a four-door Honda Accord, bound for San Francisco. And, so the cycle continued.